Welcome › Forums › M. E. Kerr & Other Topics › Vin Packer mention in writer Tereska Torrès' Obit

Tagged: vin packer

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 12 years, 6 months ago by

Michelle Koh.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

September 26, 2012 at 6:51 pm #508

Michelle Koh

KeymasterHere’s the mention with the full obituary following it:

“[Tereska Torrès’] ‘Women’s Barracks’ really launched the modern genre of the lesbian paperback,” Susan Stryker, who discussed the novel in her 2001 book, “Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback,” said in a telephone interview on Monday. “It paved the way for the next entry into the genre, which was Vin Packer’s ‘Spring Fire.’ ”

(Published in 1952, “Spring Fire” tells the story of love between college sorority sisters. Vin Packer is a pseudonym of Marijane Meaker, today widely known for her novels for young people written under the name M. E. Kerr.)

September 24, 2012Tereska Torrès, 92, Writer of Lesbian Fiction, Dies

By MARGALIT FOX

Tereska Torrès, a convent-educated French writer who quite by accident wrote America’s first lesbian pulp novel, died on Thursday at her home in Paris. She was 92.

Her family announced the death.

Though she wrote more than a dozen novels and several memoirs, Ms. Torrès remained inadvertently best known for “Women’s Barracks,” published in the United States in 1950 as a paperback original.

The book is a fictionalized account of the author’s wartime service in London with the women’s division of the Free French forces. Though its sexual scenes appear tame to 21st-century eyes, the author’s forthright depiction of the liaisons of the women in her unit with male resistance members — and with one another — scandalized midcentury America.

Originally published by Gold Medal Books, “Women’s Barracks” has sold four million copies in the United States and has been translated into more than a dozen languages. It was reprinted in 2005 by the Feminist Press in its Femmes Fatales series, which features pulp, noir and mystery novels by women of the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

The new edition gleefully retains the book’s original cover, which all but screams “salacious.” It depicts comely military women, most of them very much out of uniform, with the two most prominent clad in vivid pink bras and little else.

In the United States, “Women’s Barracks” was condemned in 1952 by the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials, which found the book’s offending passages too lurid to quote in its official proceedings.

The committee stopped short of banning the novel, however, because it was at least partly redeemed by the voice of its censorious narrator, who condemned the action as it unfolded. Ms. Torrès’s publisher, fearing an obscenity trial, had asked her to add just such a narrator before the book went to press.

In Canada, “Women’s Barracks” was banned after a trial in Ottawa in 1952 at which the Crown prosecutor called it “nothing but a description of lewdness from beginning to end.”

The book’s reception, and its subsequent enshrinement as a lesbian literary landmark, bewildered and irritated Ms. Torrès, who was married for many years to the writer Meyer Levin. In interviews, she expressed dismay at what she saw as the public’s disproportionate fascination with the novel’s scenes of erotic love between women at the expense of all else.

“There are five main characters,” Ms. Torrès told the British newspaper The Independent in 2007. “Only one and a half of them can be considered lesbian. I don’t see why it’s considered a lesbian classic.”

And yet it was.

“ ‘Women’s Barracks’ really launched the modern genre of the lesbian paperback,” Susan Stryker, who discussed the novel in her 2001 book, “Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback,” said in a telephone interview on Monday. “It paved the way for the next entry into the genre, which was Vin Packer’s ‘Spring Fire.’ ”

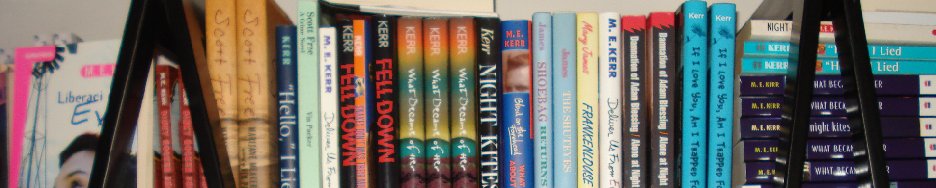

(Published in 1952, “Spring Fire” tells the story of love between college sorority sisters. Vin Packer is a pseudonym of Marijane Meaker, today widely known for her novels for young people written under the name M. E. Kerr.)

Ms. Torrès’s personal narrative was far more dramatic than anything in her fiction. She was born Tereska Szwarc in Paris on Sept. 3, 1920. Her father, Marek, a prominent painter and sculptor, and her mother, Guina Pinkus, a novelist and poet, were Jews from Poland. Before her birth, they had settled in France, and — in secret, so as not to antagonize their families — converted to Roman Catholicism and sent Tereska to a convent school.

When Tereska was 13, as she recounts in a memoir, “The Converts” (1970), news of her parents’ conversion was reported in the world Jewish press, alienating their relatives in Poland. But though the family practiced its Catholicism openly from then on, they knew it would not be enough to save them once the Nazis occupied France in 1940.

They fled to Portugal and on to London, where Tereska enlisted in General Charles de Gaulle’s Free French forces; assigned to secretarial duties, she rose to second lieutenant.

In London, she fell in love with Georges Torrès. A French Jew also serving with the Free French, he was the stepson of the former French Prime Minister Léon Blum, who had been imprisoned by the Germans in Buchenwald.

After a brief courtship, the couple were married in 1944; Georges Torrès was killed in action in France several months later. By this time, Ms. Torrès was pregnant. At war’s end she returned to Paris, where, despondent over the loss of her husband, she attempted suicide.

In 1948, Ms. Torrès married Mr. Levin, a friend of her parents 15 years her senior. Riveted by her stories of life with the Free French, he encouraged her to turn her wartime diary into a novel. He translated the manuscript from French into English and arranged for it to be acquired by Gold Medal, the one American publisher willing to touch it.

Ms. Torrès’s other novels in English include “Not yet …” (1957), “The Dangerous Games” (1957) and “The Golden Cage” (1959). The Feminist Press has just reprinted her 1963 novel, “By Cécile,” about a woman who appropriates her husband’s mistress.

A memoir by Ms. Torrès, “Mission Secrète,” about her work rescuing Ethiopian Jewish children in 1984, was published in France this year.

Mr. Levin, a writer whose novels include “Compulsion,” based on the Leopold and Loeb case, died in 1981. Ms. Torrès is survived by a daughter from her first marriage, Dominique Torrès; two sons, Gabriel and Mikael, from her marriage to Mr. Levin; a stepson, Eli Levin; six grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

It was not homophobia that caused Ms. Torrès to find her book’s canonical status peculiar. Quite the contrary, she said: because affairs with barracks mates were so much a part of ordinary wartime experience the hoopla seemed simply prurient.

“The book spoke very delicately about the few matters of sexual encounters,” Ms. Torrès told Salon.com in 2005. “But so what? I hadn’t invented anything — that’s the way women lived during the war in London.”

She added: “I thought I had written a very innocent book. I thought, these Americans, they are easily shocked.”

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.